Major League Rail (part 1)

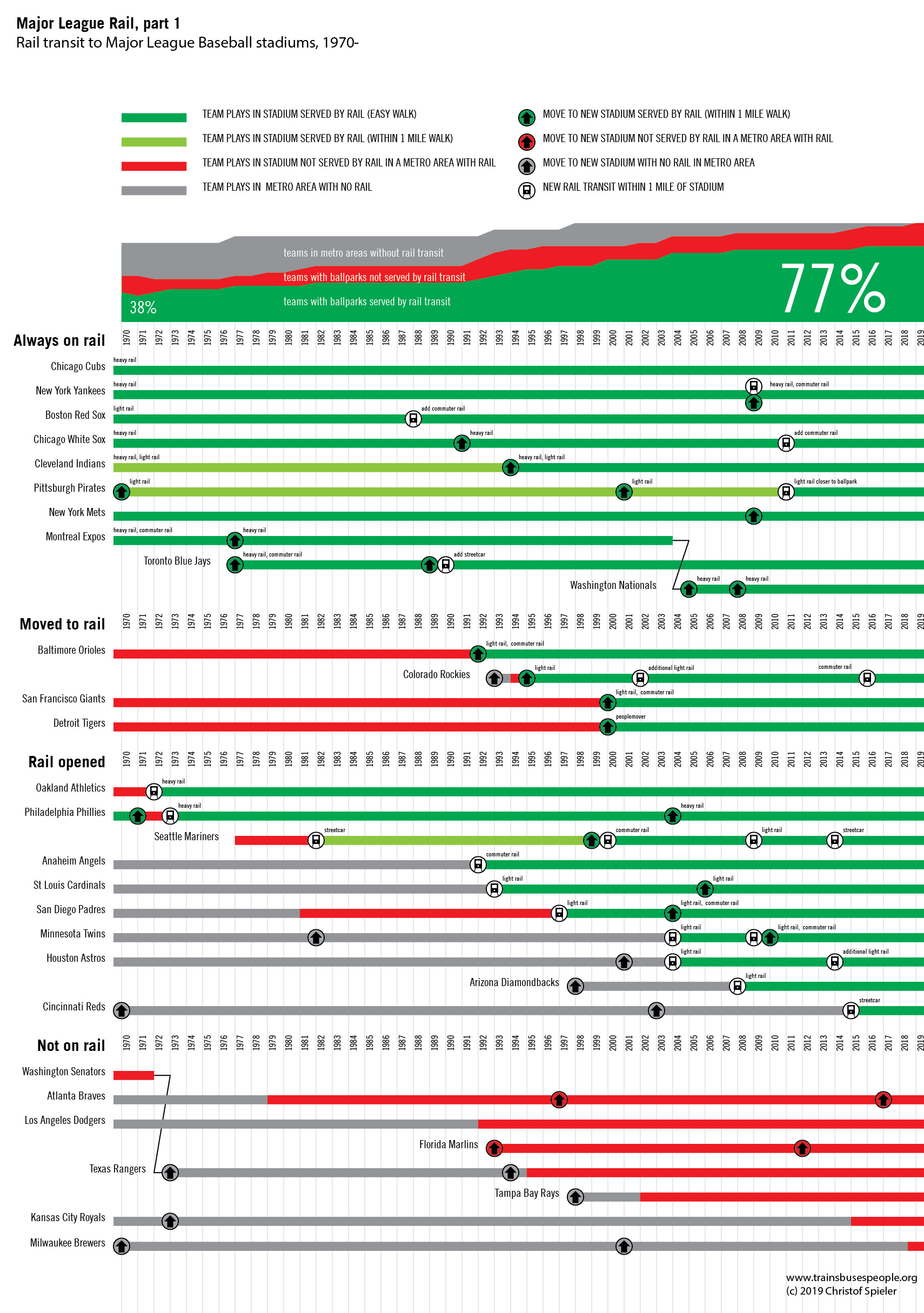

In the past two decades, the United States has seen a boom in ballpark construction. Two thirds of the current Major League Baseball venues were opened in the last 20 years. The expectations of what a ballpark looks like have completely changed. And so, it seems, have the expectations on how to get there. In 1970, 38% of baseball parks had rail transit access; today it is 77%.

Part of this change has been driven by baseball returning downtown. In San Francisco, for example, the Giants replaced a suburban stadium surrounded by parking lots with a downtown ballpark next to existing commuter rail and light rail lines.

But they real change in rail to baseball has been the opening of new rail lines. That was happening as early as the 1970s in Oakland and Philadelphia, but it really picked up pace in the 1990s. In St. Louis, Minneapolis, Houston, Seattle, and Arizona, the city’s first rail line included a stop near the ballpark. Some of this is coincidence: the national trend has been towards downtown ballparks and rail systems invariably connect to downtown to serve its employment base. It’s also an index of just how common rail transit has become: once Milwaukee's streetcar opens, every city that has major league baseball will have rail transit. But baseball is often featured in the discussion around planning new lines. It is one of the destinations that politicians and transit planners focus on.

Does it make sense to build transit to baseball? Logistically, sports venues are the worst kind of transit destination: most of the time, there are no riders, and every once in while, there are very many. A major employment center, a college, or a hospital will do much more to drive ridership. However, sports tends to add riders on weekends and evenings, when stations have capacity and spare trains are available. More significantly, perhaps, serving a ballpark draws occasional riders to the system. If they have a good experience, they might ride more often or, equally significantly, vote “yes” in the next transit referendum. A rail line built to serve only sports is hard to justify as a use of public dollars (just as stadiums themselves can be hard to justify), but if a stadium is on the way to other destinations it will make a rail line more successful.

Regardless of merit, the connection between baseball and rail seems to be well established. The Atlanta Braves’ move to the suburbs in 2017 was an anomaly, just as their current ballpark, close to downtown but surrounded by parking lots and a long way from rail, was. The last team to move their home away from rail before was the Phillies in 1971, and an extension to their new stadium was already in the works.