Ideas, not just infrastructure: what the US could learn from the Munich S-Bahn

When we talk transit, we tend to talk about infrastructure. But that's only part of what makes successful transit. The Munich S-Bahn is a case in point. It's a remarkable success that carries 800,000 passengers a day (that’s LIRR and New Jersey Transit combined) in a metro area of 2.6 million (roughly the same as Pittsburgh, a tenth of NYC). But that didn't happen just because of infrastructure.

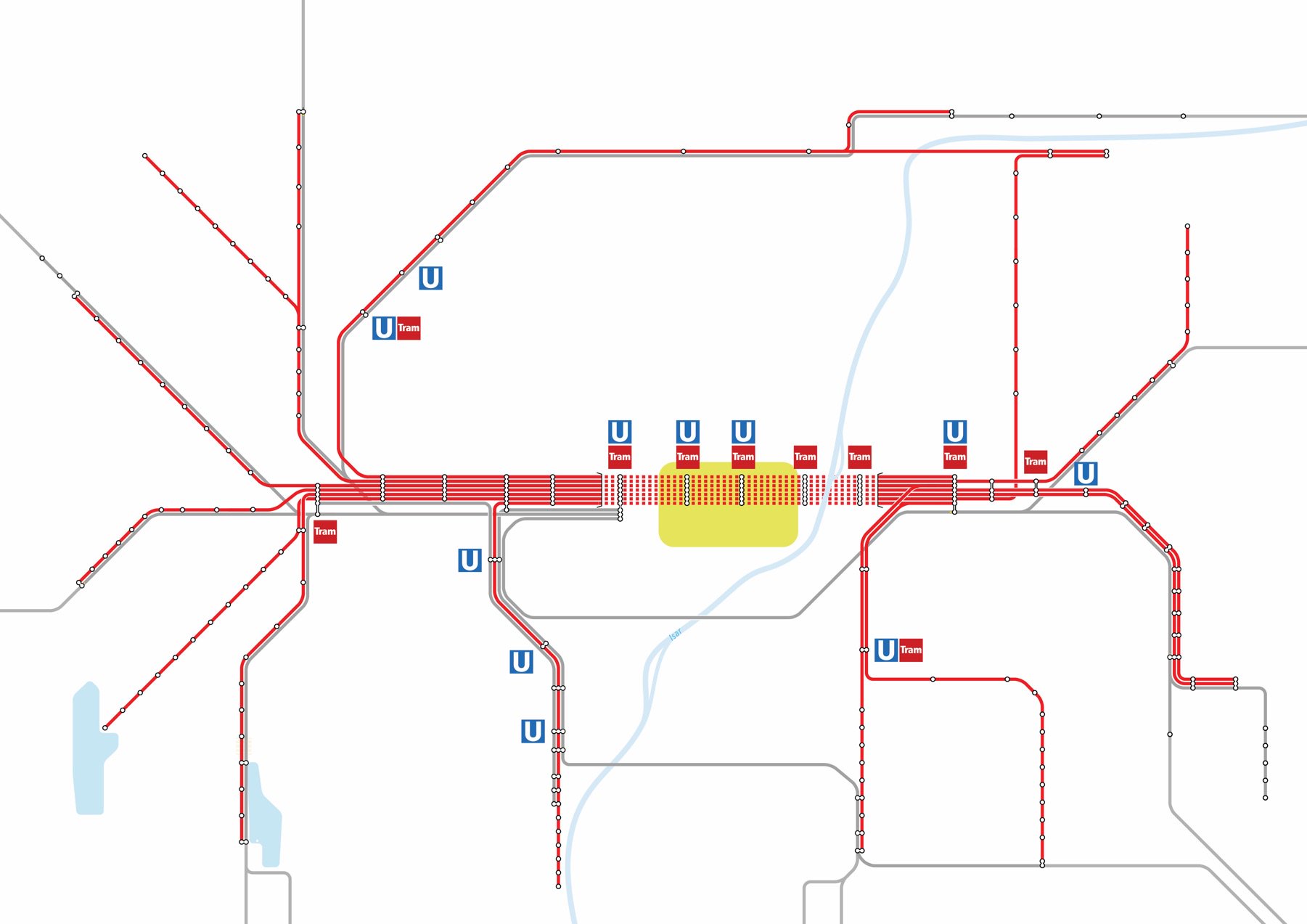

Munich did five different things to create this system: a downtown tunnel (at the left below, going beneath the stub-end Hauptbahnhof), upgraded infrastructure, increased frequency, transit connections, and unified fares.

1: A big piece of infrastructure – a new tunnel under downtown opened in 1972. Before the S-Bahn, commuter trains ran into a stub end station at the edge of downtown; now they continue through, stopping at four new underground stations in the center of the downtown. This was a huge step forward – you don’t have to transfer anymore; the train takes you to the middle of things. It’s been done in Philadelphia and considered in Boston. But, while the tunnel is the most obvious thing that makes the S-Bahn, it’s maybe not even the most important.

2: Upgrades to other infrastructure. S-Bahn stations are level boarding. The trains have 6 doors per car, and the new ones are open gangway. Some S-Bahn lines have their own tracks to avoid interference from other passenger and freight trains.

3: Dramatic frequency increases. Base 7-day-a-week service on most lines: 20 minutes. Compare to Boston, a larger metro area, where most lines less then a train an hour at midday and on weekends. The tunnel has a train every 2 minutes at peak, every 4 minutes off-peak.

4: Transit connections. The S-Bahn connects at multiple locations to U-Bahn (subway) and Tram, and at nearly every station to bus. These are not incidental connections – both bus and rail networks were deliberately planned to meet S-Bahn stations. In both the urban core and in the suburbs, these connections are designed to be as seamless as possible – underground concourses, transit centers under large roofs, and bus bays right next to station platforms.

5: Fare integration. This is what has made these transit connections work since the 1970s. One ticket covers all modes. A trip from A to B costs the same by S-Bahn, U-Bahn, tram or bus. Transfers are included. And everything is proof of payment, so there are no faregates.

Together, these 5 things are transformative. The S-Bahn improved suburban work trips into Downtown, created a new urban subway line, made it much easier for people in the suburbs to go downtown for education, shopping, and leisure, even made it easier to move within the suburbs. There are park-and-ride lots. But most of the riders arrive on foot, on a bike, on a bus, on a subway, or on a tram. The S-Bahn isn’t niche transit; it’s basic all-purpose transit across the metro area. This is commuter rail technology, but not used just as “commuter rail.”

This is what you get when you stop thinking about “commuter rail” and start thinking about “regional rail” – the S-Bahn is a new way of thinking about transit more than it is new technology. This isn't just a German idea. The same idea has been applied elsewhere — Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Paris, Tokyo, Copenhagen, London. But it hasn't been done in the United States.

That S-Bahn of thinking is very relevant to the United States. Consider New York City – it has a higher density around commuter rail stations than Munich does, and high capacity infrastructure in place. With new equipment + new fares, LIRR, NJT, and Metro-North could operate S-Bahn like service, and that would benefit hundreds of thousands of riders.

Not every commuter rail line should be an S-Bahn. The ridership will only be there if a line serves dense walkable places, not industrial corridors or low density sprawl. And if there’s major freight rail use the cost of upgrading a line may not be worth it. …but there are corridors all over the US that should be. NYC, Boston, Philadelphia, MARC Penn, Metra Electric, and Caltrain are obvious. All have exist. infrastructure and densities higher than many US light rail systems. TRE, parts of Metrolink, and Coaster might work, too.

The city that’s closest: Denver, whose A Line runs every 15 minutes, all day, every day, uses same POP ticketing as light rail (with free transfers to bus), and has bus/rail transfers at multiple stops. It’s also one of the highest performing commuter rail lines in the US.

We tend to focus a little too much on transit infrastructure. That matters, but a good transit system combines infrastructure, service, and connectivity. That’s what the S-Bahn does, and it’s hard to imagine Munich without it.