Transit Tour Guide:

Vancouver

No North American city has been transformed around transit as much as Vancouver has. The metro area has doubled in size since 1981, and much of that growth has been in the form of high-rise residential towers clustered around Skytrain stops. A former industrial city has become a model for urban planning, one of the most diverse cities in North America, and, by some measures, one of the most ”livable” places on earth. Transit is at the center of that. 90% of residents in Vancouver city limits live within walking distance of frequent transit. Over half of trips within the city are made by walking, biking, or transit, and car use is actually dropping. Transit ridership has been rising steadily for decades, up 23% in the last 5 years alone.

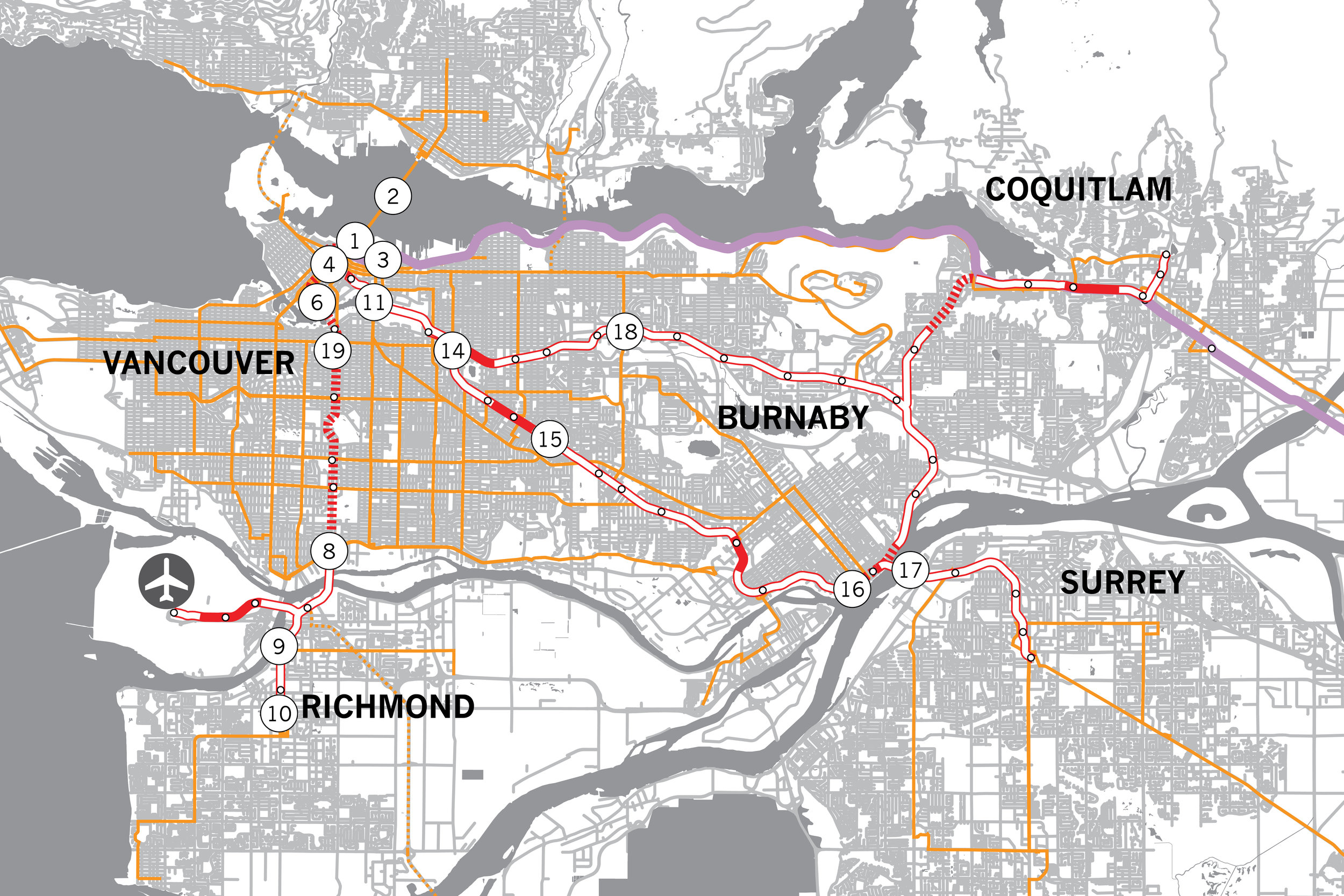

Waterfront Station [1] is the only place where all of Translink’s modes — Skytrain heavy rail, Seabus ferry, West Coast Express commuter rail, B-Line rapid bus, and local bus (in both diesel and electric trolleybus varieties.) and trolleybus — come together. The station building was built in 1914 by Canadian Pacific Railroad as the western terminus of its transcontinental line, but all intercity trains were consolidated at Pacific Central Station, at the southern edge of downtown, in 1979. By then, though, SeaBus service had started, and it was joined in 1985 by the first Skytrain line, in 1995 by commuter rail service, and in 2009 by a second skytrain line.

SeaBus [2] is one of only two passenger ferry services in North America that operate every 15 minutes or better all day on weekdays. (The other is on the other side of Canada, in Halifax.) The entire operation is designed for frequency. Unlike most ferries, which tie up at conventional piers using ropes, the seabus docks, using engine power to hold it in place in a U-=shaped pier that matches the shape of the boat. Wide doors on both sides open automatically to let passengers walk directly on and off. The stop at each end takes only 3-5 minutes; the double-ended boat then reverses out for the 10-12 minute trip across Burrard Inlet to North Vancouver. SeaBus is fully integrated into the transit system. Not only are transfers to bus and train free, but the Waterfront Station terminal connects directly to Skytrain through a covered walkway, and the Lonsdale Quay terminal is directly across a pedestrian plaza from a major bus transit center. Waterfront Peak, two blocks from Lonsdale, has great views of Downtown Vancouver; It’s a great place to be at sunset.

West Coast Express is something of a footnote in Vancouver transit, carrying less than 1% of Translink ridership on its single 43 mile line. At 6,600 boardings though, the ridership per mile is still above average for North American commuter rail. There are 5 trains inbound in the morning on weekdays only; those same trains then return outbound in the afternoon. (With each train making only two trips a day, there are more seats installed in the fleet of 44 double deck cars than there are people making the round trip commute every day.) There’s a good view of the WCE platforms from the Waterfront Station walkway to the SeaBus. The Main Street bridge [3], 15 minute walk (or a short bus ride) away, allows great photos of WCE trains with the skyline behind them. (@erik_griswold points out that an easy way to ride WCE despite its mornings-inbound evening-outbound schedule is to use the Skytrain connection at Moody Centre or Coquitlam Central, taking Skytrain one way and WCE the other.)

A half mile long stretch of Granville Street [4] in Downtown Vancouver, from Waterfront through the heart of downtown, has been a bus and taxi only transit mall since 1974. Granville is also downtown’s busiest retail street and the hub of nightlife, The mall was rebuilt in 2006-2010 with wider sidewalks and shawl curbs that encourage pedestrians to cross the transit lanes anywhere,e not just at crosswalks. At peak, there’s a bus here every 80 seconds, and 82,700 riders use the transit mall on an average weekday.

The Skytrain network is remarkable in two ways.

The first is that is is the only completely automated large scale rail network in North America. Some other cities like Miami and Detroit have short people mover networks, but Vancouver is the only city operating full-sized trains on a large network with no drivers on board. This means that the cost of operating service doesn’t go up dramatically with frequency. Therefore, Vancouver can provide better off-peak frequency than any other North American rail system. Expo Line trains come every 2-3 minutes at peak on most of the line, which matches the busiest rail lines elsewhere. But, unlike those other cities, they come almost as frequently all day, every day. The least frequent service — late night until 1:00 am — is still every 5 minutes or better. The other bonus from being automated: all Skytrain trains let passengers seats look directly out the windshield [5], and the newer trains have a full row of forward-looking seats.

The second remarkable thing about Skytrain is that no other North American rail system has seen as much transit-oriented development. Suburban stations that were surrounded by one story commercial sprawl when they opened are now clusters of high-rises. The core of Vancouver is dense and walkable, but what’s most remarkable is just how urban the suburban parts of the network feel.

Technologically, Skytrain is actually two networks. The Expo and Millennium Lines, opened in segments from 1985 to 2016, use unusual linear induction technology, where a continuous wide metal strip between the rail acts as part of the motor, with the train pushing off of it through magnetic force. This allows fast acceleration and steep grades and minizes moving parts. The Canada Line, opened in 2009, uses more conventional electric third rail technology like most heavy rail lines. All three lines use relatively short trains — 250 food maximum on Expo/Millenium and 130 foot on Canada. Capacity comes from frequency, not train length.

True to its name, most of Skytrain is elevated. The original Expo Line re-used a 0.9 mile railroad tunnel under Downtown. Because the single track tunnel was relatively tall, and skytrains cars are much shorter, the two skytrains were fit into the tunnel by stacking them above each other. For most of the way from Vancouver to New Westminster, it follows an old interurban streetcar line. The remainder of the Expo Line and the Millenium line follow railroads and freight rail lines, usually elevated. The Canada Line has a much longer tunnel - nearly 6 miles from Waterfront to just north of Marine Drive. South of there, it is largely elevated; the Richmond branch is above No. 3 Road while the airport branch follows the airport access road.

Yaletown-Roundhouse Station [6[ on the Canada Line is a good example of how central Vancouver has transformed in the last 40 years. In the 1980s, this was an industrial district; now it’s a bustling high-rise residential neighborhood. Typically for Vancouver, it’s designed to be kid-friendly. There’s an elementary school in the midst of the towers and a park on the waterfront. The old Canadian Pacific Railroad roundhouse a block from the station is now a community center with extensive programs for children and adults. This is also a good spot to catch the Aquabus ferries [7] to Granville Island Public Market.

Marine Drive Station [8] has a large mixed use development and a bus transfer hub, which is one of the southern ends of the trolleybus network. (The main bus garage for the trolley buses is at Vancouver Transit Center, about a mile west on the #10 or #100 buses.)

As it crosses an arm of the Fraser River, the Canada Line enters Richmond, BC, which has the highest concentration of immigrants, mostly Asian, of any city in Canada — 60% of a population of nearly 200,000. Aberdeen Station [9] is in Richmond’s “Golden Village” shopping district. Aberdeen Center, attached to the station, has a strong Hong Kong influence.

The end of the Canada Line is at Richmond/Brighouse Station [10]. The station offers. a good view of the high-rises scattered around Richmond, once a city of single family houses and strip malls. The giant Richmond Centre Mall next to the station, one of Canada’s 10 busiest shopping malls, is about to be transformed; in 2019 the city approved a plan that will replace the high surface parking lot with 27 acres of new mixed use development. 12 new high rises, up to 14 stories tall, with 2,300 new condos and apartments.

At Science World Station [11], the elevated Skytrain tracks skirt the edge of False Creek. Creekside Park, 5 minutes from the station, has nice views of the water and the tracks. Further east along the waterfront, 10 minutes from the station, is the Olympic Village [12] for the 2010 Winter Olympics, now a residential neighborhood. On the other side of the station is Pacific Central Station [13] where Amtrak’s trains to Seattle and Via’s transcontinental Canadian terminate.

Commercial-Broadway Station [14] is where the Expo Line crosses the Millenium Line. It has a very unusual arrangement. The Great Northern Railroad line, still active with freight and passengers trains, was built through here in 1915 in the deep Grandview Cut, blasted through solid rock. The cut is so deep that, even though the Millenium line is elevated above the railroad tracks, it is still below ground level. The street then cross over both the rial road and the Millenium Line on. a bridge, and the Expo Line station is elevated above street level.

Joyce-Collingwood Station [15] is typical of the first generation of Skytrain stations. Big parts of the surrounding neighborhood still look much as they did in 1985, but the typical Vancouver high-rises are here, too. Because it’s on a hill, the station has a great view east down the tracks.

New Westmister Station [16], opened in 1985, is in the middle of the historic downtown of New Westminster, a port city on the Fraser River that’s actually older than Vancouver. In 2012, the station was literally surrounded by the Shops at New West, a three-level shopping mall that integrates the station’s circulation. Shops are directly outside the station’s fare gates.

Nearby, the Skybridge [17] brings Skytrain cross the Fraser River. At 1,120 foot, it’s the longest transit-only span in North America. There are great view of the bridge from Westminster Pier Park, a short walk from Columbia Station (or a somewhat longer walk from New Westminster Station.)

Brentwood Town Center [18], where the Skytrain station hangs over a six lane arterial, is a landscape in the midst of transformation. Gas stations and car dealerships, typical of what was here before the train, remain. Around them are new residential high-rises, and the mall parking lot is being transformed into a mixed use district.

The 99B bus on Broadway [19] is the busiest bus route in North America, with 55,900 passengers on an average weekday. It’s a limited stop rapid route anchored at one end by the campus of the University off British Columbia at the westernmost tip of Vancouver. It runs down the busy Broadway commercial corridor, connects to the Canada Line at Broadway/City Hall (also the location of Vancouver General Hospital), and ends at Commercial/Broadway station on the Expo and Millennium lines, a total of 8.9 mies. At peak, 60 foot articulated buses run every 3 minutes; in the middle of the day there’s a bus every 4-5 minutes, and even at 11:00 pm there’s still a bus every 10 minutes. This is all in addition to the local buses that use the same street. But even at that frequency the route is stretched beyond capacity; the City of Vancouver estimates that 2,000 people a day at Commercial/Broadway find no room on the first bus and have to wait for a second. In 2020, construction will start on a Skytrain extension that will run 3.6 miles along the central part of Broadway. The city hopes to further extend that to UBC.

Like its US neighbors, Alaska and Washington State, the province of British Columbia operates a major ferry system, with 36 boats on 30 routes. Unlike in Seattle, where state ferries docks right on the downtown waterfront, none of the BC routes go into Vancouver. Instead, ferries dock at Tsawwassen south of the city, near the US border, and Horseshoe Bay in West Vancouver [20], to the north, Both of these terminals are served by Translink buses.

Getting around

Translink has a zone fare system. All buses count as Zone 1, but Skytrain extends across three zones and SeaBus crosses two, All weekend and evening trips count as a single zone. A day pass across all zones is $10.50 Canadian.

Compass smart cards are sold at all Skytrain stations (including the airport) and can be loaded with value or day passes. In addition, all buses, trains, and ferries accept Apple Pay, Google Pay, and contactless credit cards.

The Mobi bikeshare system covers downtown and the surrounding neighborhoods with 143 stations and 1,400 bikes. Unlike most bikeshare systems, though, you can’t just walk up to a station with a. credit card; using the system first requires registering online or downloading the app.

Getting there

The Canada Line runs from the airport to Downtown Vancouver.

It’s easy to combine a trip to Vancouver with a trip to Seattle and/or Portland, both cities with transit that’s worth seeing. Amtrak offers two Cascade round trip trains a day between Vancouver and Seattle (a three hour trip.) One train in each direction goes as far as Portland. Amtrak also offers another four bus round trips to Seattle (with train connections on to Portland.) Greyhound, Bolt, and Quick Shuttle also make the same trip.