METRONext and the keys to successful transit

The Houston METRO board is considering what the next two decades of Houston transit will look like. A draft METRONext plan was released for public comment in January, and the board is aiming to put a final version on the ballot in November.

In my book (“Trains, Buses, People: an Opinionated Atlas of US Transit”) I talk about what makes transit networks successful -- and what we often get wrong. So how does this plan do?

The plan includes four major elements:

A light rail and BRT network, adding to the 3 light rail lines that already exist and the one BRT route under construction (above), all with dedicated lanes, level boarding, off-board fare collection, and service every 12 minutes or better. (This is really one network, even it uses two technologies. All these lines are intended to offer the same level of frequency, speed, reliability, convenience, and comfort. In some cases, trains and BRT buses will even share lanes and station platforms. We can have some discussions on which lines should be BRT and which should be light rail, but I’ll leave that to another day.)

A network of regional express buses in freeway corridors, converting the peak-focused, downtown-focused Park and Ride network into 7-day-a-week, all-day 2-way service.

A network of frequent local buses, running every 15 minutes or better, improving on the frequent routes that were put in place in 2015 with better stops, faster and more reliable service, and added frequent routes.

The basic network of local buses, running either half hourly or hourly.

Proposed METRONext network.

POPULATION

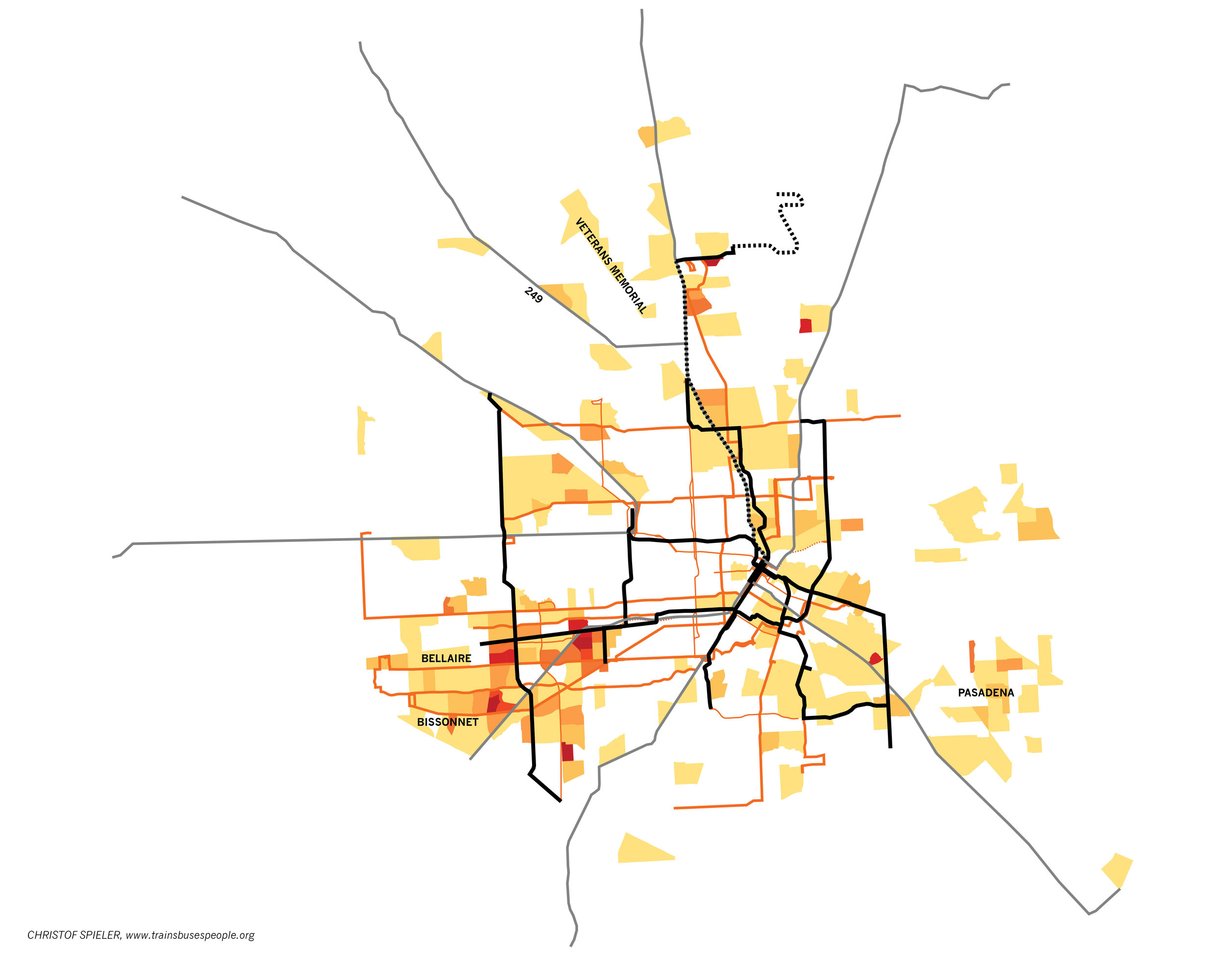

The single most important element of transit ridership is population density. The more people who live within walking distance of transit, the more will ride it. Unlike a lot of US rail systems, the proposed light rail and BRT lines stick to areas with reasonable density, and, combined with frequent buses, they cover the urban core well.

Population density with proposed METRONext network.

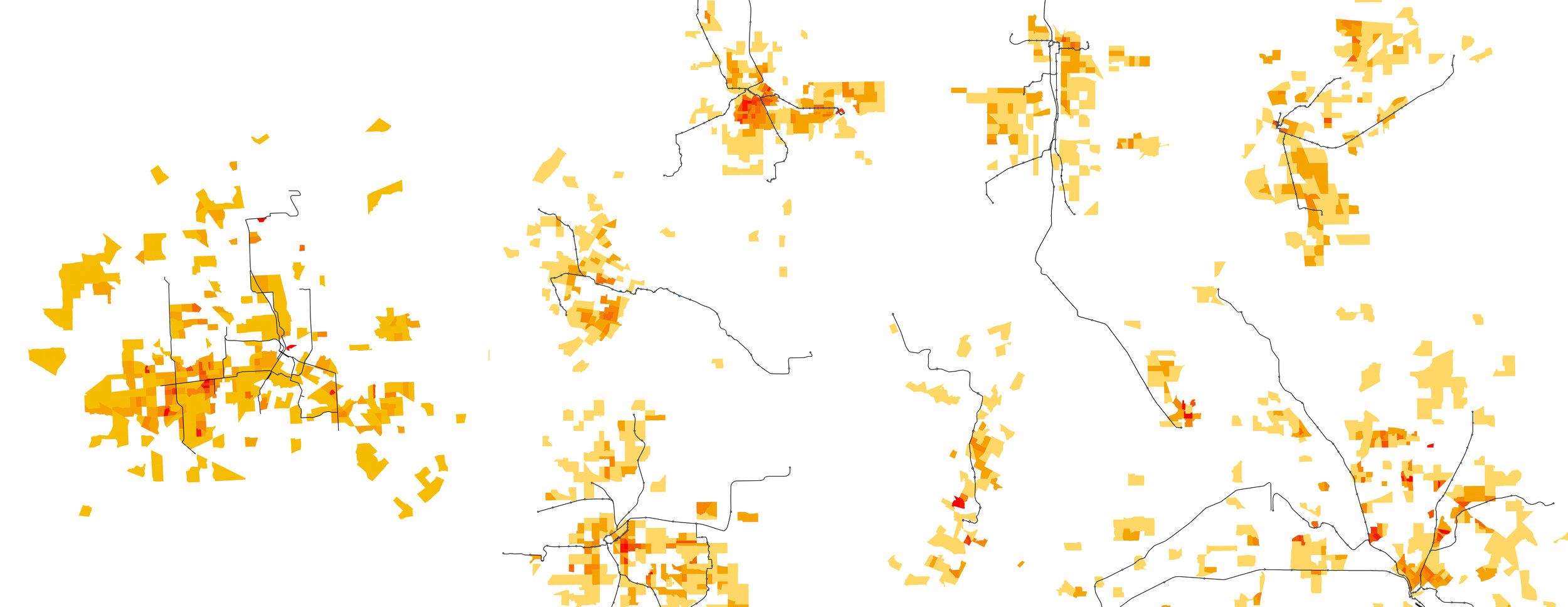

Rail and BRT lines on population density: METRONext plan (left). St. Louis, Denver, Twin Cities, Salt Lake City, Sacramento, Dallas.

It’s also worth looking at how well the network serves low income residents -- the people who benefit most from better transit. Here’s a map of low income population density -- number of low income residents per square mile. In Houston, many of the densest places, like the apartment complexes of Greenspoint and Gulfton, are actually low income. This map shows that this network serves low income areas very well. Unlike many other systems, the METRONext plan is not focusing investment more affluent suburban commuters while ignoring low income residents.

There are gaps in frequent transit coverage. The most obvious isn’t METRO’s fault: Pasadena decided not to join METRO in 1978 and has no bus service at all. There are other areas though, where it more frequent bus service could be justified, including areas along Veterans’ Memorial and 249, where buses are currently running every 30 minutes. (High performing 30 minute routes in parts of town that already have some frequent service probably merit more frequent service, too -- LINK Houston did a good analysis of that.) There are also places in Southwest Houston that might justify rail/BRT, such as the Bellaire and Bissonnet corridors west of the 59. These have much higher density than the southeast neighborhoods served by the double light rail lines to Hobby Airport.

Low income population density with proposed METRONext network.

ACTIVITY

But of course transit where someone lives isn’t enough -- it needs to go to where they work or go to school, and all the other places they need to go in the course of a day. The most successful transit lines are those that connect multiple activity centers. That’s why the original section of the Red Line has such high ridership -- it links two major employment centers (Downtown and TMC) along with multiple universities and other destinations like the stadiums and museums. The Purple Line added UH/TSU to the network. BRT is now under construction in Uptown, but it doesn’t connect to the rest of the Rail/BRT network.

Activity centers with current and under construction rail/BRT network.

Connecting activity centers is an explicit goal of METRONext, and it shows. The plan connects the newt two biggest employment centers -- Uptown and Greenway Plaza -- to the Rail/BRT network as well Westchase and Greenspoint. It also adds a second line to US and TSU, serving more parts of both campuses and creating a new cross-town connection.

The apparent omission is the Energy Corridor. But it is not the same kind of place that Uptown, Greenway Plaza, and even Westchase are. Rather than being centered on a street, it’s centered on a freeway, and it’s spread out over nearly 10 miles. It isn’t a place built so that transit works well. But if employers provide shuttles to the central hub of Addicks P&R, it might justify extending BRT along the Katy Freeway toll lanes with a stop (already proposed in the plan as part of the regional express network) at Gessner to serve the offices, hospital, and mall at Memorial City.

Activity centers with proposed METRONext rail/BRT/regional express network.

CONNECTIVITY

Another trait of successful rail and BRT networks is that they connect to bus networks, making them useful to many more people.

METRONext does this on two levels.

The first is the regional express network. We’ve undervalued the park-and-ride buses -- they carry more people than any post-WWII commuter rail network in the United States, and they’re the main reason why a third of Downtown employees use transit. So think of it as our version of commuter rail -- the system that links to the suburbs to the core. METRO Next makes the network more useful by adding service. That means you have better options if you have to work late or on the weekend, and that it will also be useful for going to a baseball game or the museum. METRONext also makes the regional network more useful by connecting it to more places. At key points (yellow dots) the regional express buses connect to rail/BRT, creating links from the regional network to activity centers. That means people who work in other employment centers will be able to take advantage of the same service people in Downtown are already using. Someone coming from Katy, for example, would be able to ride the regional express to Downtown, but they would also be able to get off at Gessner to get to Memorial City or take BRT to Westchase, get off at Northwest TC to take BRT to Uptown, or connect in Downtown to light rail to the TMC or UH. Someone leaving near Downtown would be able to take the some service out to the Energy Corridor.

There are a dozen connection points between the regional express and rail/BRT networks. But there are some useful connections that aren’t in the plan:

In Southwest Houston, the Gessner BRT crosses IH-69 regional bus without a connection between the two networks. There’s no good existing infrastructure to make that connection – the Westwood Park-and-Ride is 1 ½ miles away – but if a new regional express stop were added in the freeway commuters from Fort Bend could get to Westchase, and residents of Southwest Houston would have faster connections to Downtown. At Wheeler Transit Center, where Southwest Freeway Express buses pass two blocks away from the existing light rail station and the new BRT station. A connection here would set up convenient connections from the regional express buses to the TMC, UH, and TSU.

The Gulf Freeway regional express buses come within a mile of Hobby Airport and the two light rail lines serving it, but the closest connection point is 10 miles away, in Downtown. This gap could be filled by extending light rail a little less than 2 miles to Monroe Park and Ride, or by adding a freeway bus station where IH45 crosses Broadway.

Proposed METRONext network: connectivity between Rail/BRT and regional express.

The second level of connectivity is to the local bus network. One of the keys to reimagining the Houston bus network was the connection between bus and rail. The rail lines are an integral part of the network, providing high capacity spines that allow bus riders people headed Downtown or to the TMC to connect to rail for faster and more reliable trips.

The proposed rail and BRT lines set up many of these connections. Every yellow do on this map is a connection from rail/BRT to frequent bus; the large dots are transit centers (new or existing) and the small ones are stations with connecting bus service. This shows only the frequent bus routes; there are many more connections to half hourly or hourly local bus service.

Proposed METRONext network: connectivity between Rail/BRT and frequent bus.

METRONext is not just a collection of new lines; it’s a connected network. Nearly every bus route in Houston would have a connection to rail or BRT. The benefits of these projects would extend far beyond their physical footprints.

Diagram of METRONext frequent transit network.

PEOPLE

All three of these ways to look at a network -- density, activity, connectivity -- are really ways to measure how useful transit is to people.

The best measure of how useful transit is has always been, and will always be, ridership. People using transit is a sign that route or network is serving a useful purpose -- getting them to a job, to school, to the grocery store, to church, to the park.

With that in mind, it’s always worth asking where transit is useful today.

The best opportunities to grow transit ridership are places where people are already using transit. If there’s enough demand to fill a local bus with minimal stop amenities that gets struck in traffic, there will definitely be more demand for faster, more reliable, more convenient, and more comfortable service.

One of the biggest problems with transit planning in the United States is that it doesn’t take existing ridership seriously enough. In general, we’ve valued new riders over making trips better for existing riders, and we’ve invested hundreds of millions in rail lines in places that don’t justify an hourly bus. It’s remarkable how many cities have rail, but not in their busiest transit corridor. If for the last 30 years the federal New Starts program, with all its required analysis, had simply been replaced by a program that give agencies money to convert their busiest bus routes to rail or BRT, we’d almost surely have higher national transit ridership than we do.

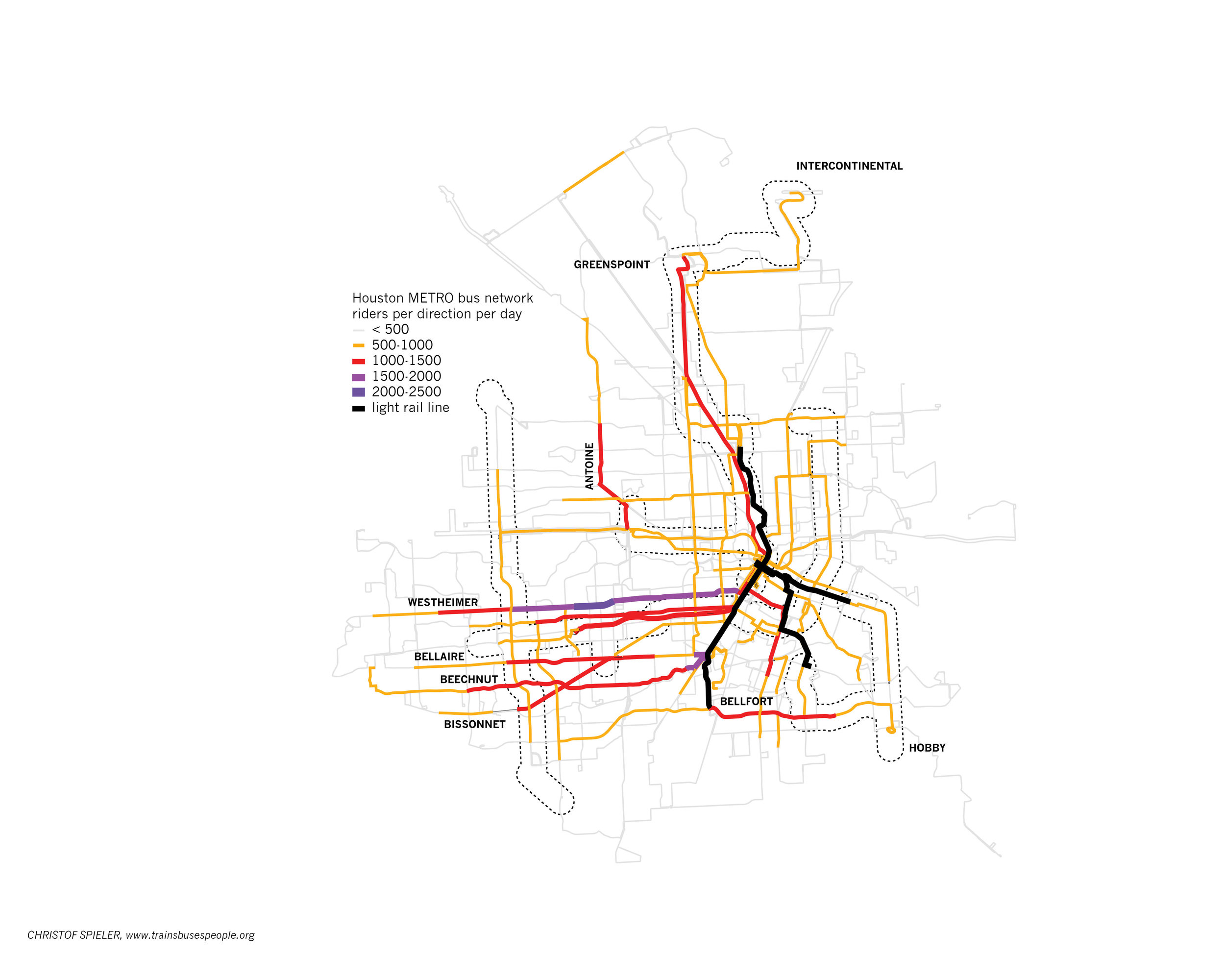

Current METRO bus ridership.

That is possibly the most remarkable part of this proposed network. METRONExt is the direct follow up to the reimagined bus network. Here’s a map of METRO bus ridership -- how many passengers a day pass each point. (This is based on data I got from METRO.) The ridership patterns make a lot of sense when compared to the population and activity maps above.

The current frequent network shows through as the higher ridership routes. The maps also shows clearly how the Main Street line acts as part of the bus network -- look at all the high ridership routes leading right to rail.

This map shows the METRONext rail and BRT corridors overlaid on current bus ridership. Note how much the two match, and how many of the high ridership routes get new rail/BRT connections. METRONext is focusing on corridors that are already strong transit corridors, and making them better.

Here, too, we can see some possible gaps. Bellaire, Beechnut, and Bissonnet in Southwest Houston might be good BRT corridors. Antoine north of 290 might be a logical extension of the BRT line to Northwest Mall -- it showed up in the MetroNEXT vision plan but was cut to fit the cost constraints of the “moving forward” plan. The same goes for Bellfort from Fannin South to Sunnyside. This maps also shows just how strong the ridership on outer Westheimer is -- the busiest bus route in Houston is not in Downtown or in a walkable streetcar neighborhoods abut amongst the strip malls and apartments between Uptown and Westchase. Westheimer outside the loop would be a strong BRT or rail corridor, and the space is there on that 8 lane stroad.

This map shows the strength of the BRT line to Intercontinental Airport via Greenspoint — the current 102 express bus to Greenspoint is already a high performer. It also shows both why Hobby Airport really needs only 1 rail line, and why it’s hard to choose only one — no one route to the airport stands out. The new proposal reduces the cost here, but it actually follows corridors with lower current transit ridership, and the investment in light rail in the Southeast still seem out of proportion to demand, especially considering the high ridership corridors in the Southwest that get neither rail nor BRT.

Current METRO bus ridership with METRONext rail/BRT overlaid (dashed outlines).

As METRO prepares for an election on his plan, there will surely be critics who point to places like Dallas and say that rail or BRT doesn’t work in sprawling sun belt cities. That’s silly. Houston is sprawling, but it has lots of dense neighborhoods and major activity centers where transit can work well. We have one of the highest ridership light rail lines in the country, and we’re one of the few places where bus ridership has been growing. The cities which have low ridership rail systems don’t have low ridership rail systems because rail doesn’t work, or because the cities are inherently unsuited to rail; they have low ridership rail systems because they put rail in the wrong places.

The METRONext plan focuses on what we know makes transit work -- population, activity, connections -- and really reflects the structure of Houston: its multiple activity centers, its pockets of density, and its current transit network. The plan will -- and should -- be refined, but fundamentally, this plan creates a network that makes transit a lot more useful for many Houstonians, both those who are currently riding transit and those who aren’t.