Defining service, not mode

As human beings, we like to categorize things — it makes it easier for us to understand the world. We do that in transit, too. But sometimes these categories actually make transit systems worse.

Every metro area map in Trains Buses People has a key like this one, listing modes of transit.. These categories are very commonly used in transit, and that’s because they’re useful. A green line, for example, is a streetcar, and a red line is heavy rail. They’re very different technologies. One shares lanes with cars, one has its own tunnel. One can carry 2000 people in a train; one carries 150. The experience of riding them, the kinds of trips they’re useful for, and their role in a transit network will be different.

But mode distinctions are fundamentally made on technology, and sometimes technology isn’t what matters most.

Consider the San Francisco Bay Area, and especially BART and Caltrain.

BART is heavy rail. It is completely separated from cars, bicyclists, and pedestrians — no shared lanes, no at grade crossings — as well as freight rail. It is powered by an electric third rail.

Caltrain is commuter rail. It can (and does) share tracks with freight rail, and it can (and does) cross streets at grade. It is currently powered by diesel locomotives but is in the process of upgrading to electric power from overhead wires.

These technological differences matter. They make a huge difference in the feasibility, cost, and impact of new transit lines.

But riders care much more about where a transit line goes, how frequently it runs, whether it runs in the evening or on weekends, and how fast it is. Technology doesn’t determine those things.

Because we care about service, though, we tend to use technological categories like “heavy rail” and “commuter rail” as proxies for service.

When we say “heavy rail” we think of something like the New York Subway. It’s focused in the urban core. The stations are in walkable places, and they’re closely spaced (1/2 mile on average) so people can get to them. The service is really frequent — 10 minutes or better during rush hour, up to 15 minutes late at night and on weekends. That means people ride the subway for all kinds of trips — work, school, shopping, meeting friends, going to the park, seeing a movie — at all times of the day.

When we say “commuter rail” we think of something like LA’s Metrolink. It stretches from downtown far into the suburbs. Many stations are simply big park-and-ride lots, with few destinations within walking distance. Because the lines go so far out, the stations have to be widely spaced —- 7 1/2 miles on average — so that trips are reasonably fast. Service is heavily focused on rush hours in the peak direction; mid-day, evening, and weekend service runs every hour at best, and some lines have rush hour service only. That means nearly all the people riding are commuting to 9-to-5 jobs.

These characteristics of type of service, location, and purpose are not inherent to the technology, though. And neither BART nor Caltrain fits these archetypes well.

BART extends far into the suburbs. Much of its network is heavily based on park-and-ride. Stations average 2 1/2 miles apart. In many ways, BART is like commuter rail, using heavy rail technology.

Caltrain also has stations spaced 2 1/2 miles apart. It connects two major downtowns — San Francisco and San Jose — and many of the stations in between are in small town downtowns. Along with electric wires, Caltrain is upgrading its service. Trains already run in both directions all day; soon they may run at least every 10 or 15 minutes all day, 7 days a week. In the kinds of places it serves, and the service it will offer, Caltrain resembles many heavy rail systems, even though it is using commuter rail technology.

When we think about service and destinations, Caltrain and BART are really becoming the same thing, even though they use different technologies to do it. They will both be relatively fast, relatively long-distance, all-day, frequent services, serving trips to and between major regional centers, with connections to multiple local transit systems along the way. They are what we might call “Regional express” services.

I think that’s a useful way to think about transit — not mode, but the type of service.

Urban spine

Every 5-15 min

All day, 7 days a week

Corridors within the urban core

Stations in major activity centers and dense walkable areas

Access by walking, biking, transit connections

Stations every 1/4 to 1 mile

Reliable service in dedicated lanes or ROW

Medium speed

Commonly heavy rail, light rail, BRT

Frequent Local

Every 5-15 min

All day, 7 days a week

Corridors within the urban core

Stops in major activity centers, dense walkable areas, and medium-density areas

Access by walking, biking, transit connections

Stops every 1/8 to 1/4 mile

Less reliable service, often in mixed traffic

Low speed

Commonly bus, streetcar

Regional express

Every 10-30 min

All day, 7 days a week

Corridors stretching across the region

Stops in major activity centers, secondary centers, and park-and-rides

Access by walking, biking, transit connections, park-and-ride

Stops every 1/2 to 5 miles

Reliable service in dedicated ROW

High speed

Commonly heavy rail, light rail, commuter rail, BRT

Coverage local

Every 16-60 min

All day, 5-7 days a week

Corridors stretching across the region

Stops in major activity centers and dense walkable areas

Access by walking, biking, transit connections

Stops every 1/8 to 1/4 mile

Less reliable service in mixed traffic

Low speed

Commonly bus

Peak-only express

Every 10-60 min

Peak service focused, with minimal mid-day, evening, or weekend service.

Corridors stretching across the region

Stops in major activity centers and park-and-rides

Access by park-and-rides

Stops every 2 to 10 miles

Reliable service in dedicated lanes or ROW

High speed

Commonly commuter rail, bus

These service types reflect what role a transit line plays in the overall network. One mode — like light rail — one be deployed in different was to create fundamentally different kinds of service. That’s Dallas on the left and Houston on the right, both light rail, both using the same technology, but in a very different way to serve very different roles: look at station spacing and how far the lines extend out. (The comparison isn’t always so clear and these categories are not always so obvious — some systems combine different service types on the same system or even the same line.)

There are two good reasons to think about transit in terms of types of service.

The first is in planning. Starting a project by identifying the right type of service for a corridor — “we need regional express” or “we need urban spine” is far more useful than identifying the right kind of mode. Service is what will make a project useful. It speaks to whether people will be able to use the new line for the trips they want to make. The right mode can be a technical decision, based on the available right of way, cost, and what technologies are already in use.

The second is in helping passengers navigate a system. When someone is looking at a map, trying to decide how to get somewhere, frequency and speed matter most. That’s what transit systems need to communicate to their passengers more than mode.

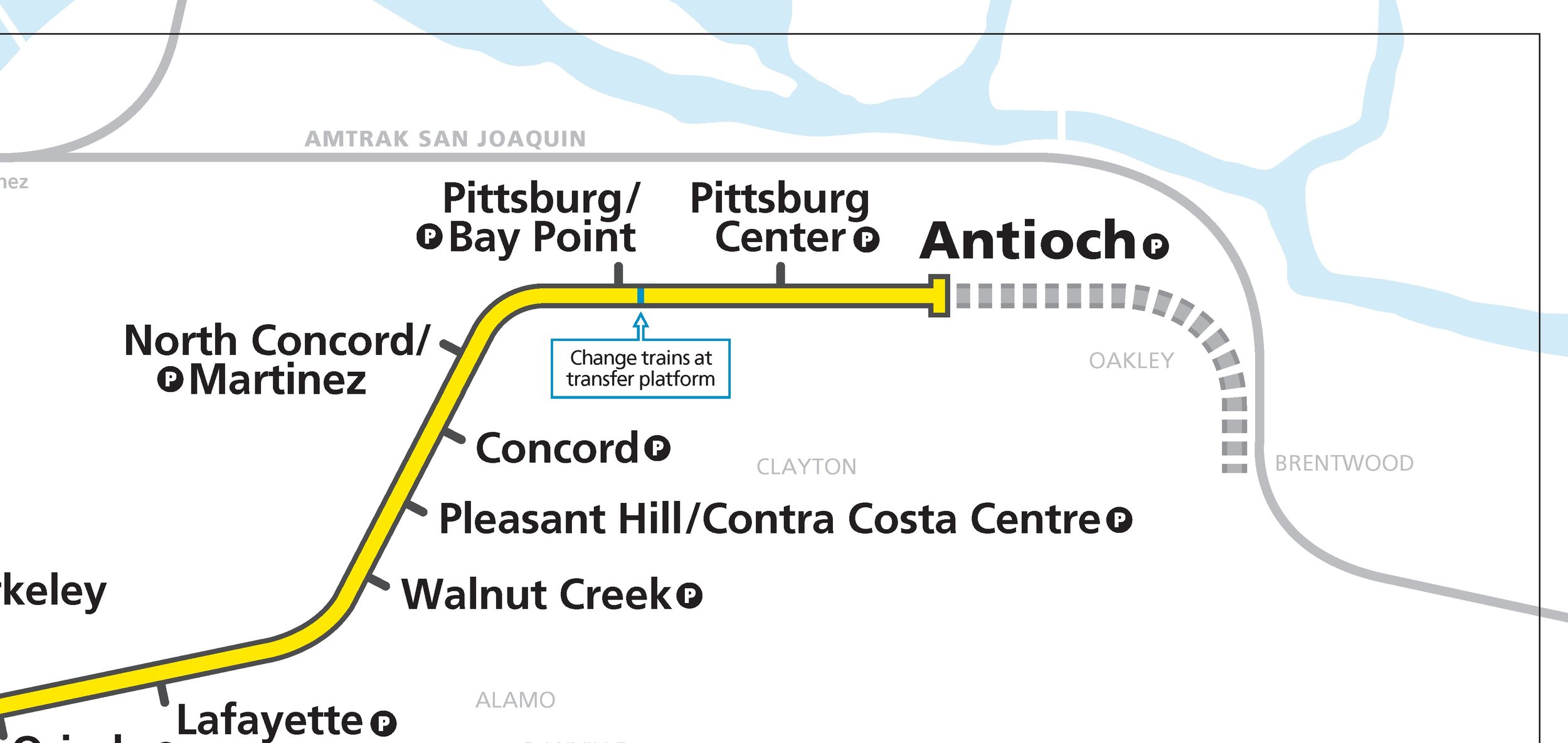

BART, as it turns out, is already doing that. The Pittsburgh to Antioch eBART uses commuter rail technology. It’s completely technologically incompatible with the rest of the BART network — the trains are shorter, they’re powered by diesel instead of electricity, and the rails are a different distance apart. But the frequency and speed of service matches the rest of the BART network. And on the system map, it looks exactly the same as the rest of BART:

I think the map is a bit dishonest in minimizing the transfers, and it’s also dishonest that the eBART trains have destinations signs that read “SFO Airport” when they will never get any closer than 35 miles from the airport. But the fundamental idea is right — eBART is BART, and it’s best communicated to passengers that way.

But BART maps treat Caltrain as if it is something completely different — a little gray line.

Right now Caltrain is different than BART, in terms of service and fares. But it shouldn't be. Fares should be integrated between BART and Caltrain (like they should be between all Bay Area transit.) Beyond that, though, once Caltrain is electrified, Caltrain is extended to meet BART in Downtown San Francisco, and BART is extended to meet Caltrain in Downtown San Jose, they will connect at multiple places and both offer similar levels of service and serve similar purposes. I think they ought to be considered one system, something like this:

This isn’t a map of all the rail lines in the Bay Area (Steve Boland has a nice one of those here). It doesn't show MUNI Metro, the F-Market streetcar, SMART, ACE, or VTA Light Rail. It’s a map of one regional express network. I’m not just saying fares should match or station transfers should be easy. I’m saying there’s no reason at all to tell passengers that Caltrain and BART are different things. They should just be one system, just like eBART and BART are one system, or like the Blue, Red, Orange, and Green lines in Boston, which have multiple types of incompatible trains, are one system. (I will note that future Caltrain service patterns are not set yet, and may actually be more complicated than this shows. Whether they should be is another discussion.)

For years, elected officials pushed to extend BART down the Peninsula. Fortunately, decision makers ultimately realized that electrifying Caltrain accomplishes the same thing at much lower cost. But if the public doesn’t understand that this new Caltrain isn’t “commuter rail,” with all the assumptions that term brings, if will not live up to its potential. Caltrain will be useful for all sorts of trips — long ones to work in San Francisco or San Jose, short ones from one town on the Peninsula to another, rush hour trips, weekend trips, evening trips, work trips, school trips, fun trips. Transit agencies need to communicate that. Ultimately, the technological difference between BART and Caltrain isn’t what matters. And if we think less about technology and more about service we will make transit easier to use.